Artificial protein shell to combat COVID-19

During the first COVID-19 wave, when Saumitra Das and colleagues were sequencing thousands of samples every day to check for SARS-CoV-2 variants as part of INSACOG, the Government of India’s genome surveillance initiative, they were racing against time to track mutations as they appeared. “If we wanted to predict whether one of these mutations was going to be dangerous from a public health perspective, we needed an assay system,” says Das, Professor at the Department of Microbiology and Cell Biology (MCB), Indian Institute of Science (IISc). The assay protocol widely followed, involved isolating the virus from the samples, creating multiple copies of the virus, and studying its transmissibility and efficiency at entering living cells. Working with such a highly infectious virus is dangerous and requires a Bio Safety Level-3 (BSL-3) lab, but there are only a handful of these labs across the country equipped to handle such viruses. To address this problem, Das and his team, along with collaborators, and with funding from the Department of Biotechnology (DBT), have now developed and tested a novel virus-like particle (VLP) – a non-infectious nanoscale molecule that resembles and behaves like the virus but does not contain its native genetic material – in a study published in Microbiology Spectrum.

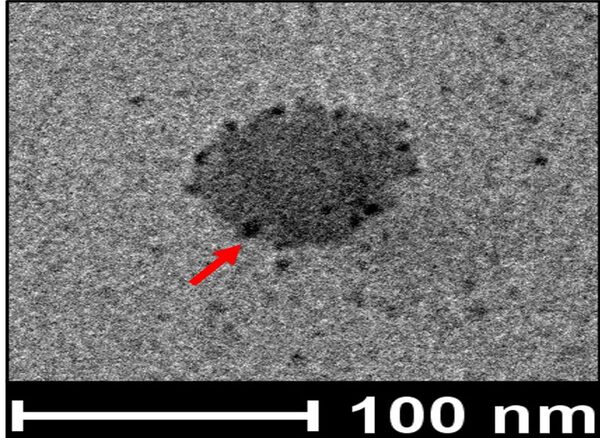

SARS-CoV-2 replicates by producing each structural protein separately and then assembling them into a shell containing the genetic material inside to form an active virus particle. To recreate this, the team chose a baculovirus – a virus that affects insects but not humans – as the vector (carrier) to synthesise the VLPs, since it has the ability to produce and assemble all these proteins and replicate quickly. Next, the researchers analysed the VLPs under a transmission electron microscope and found that they were just as stable as the native SARS-CoV-2. At 4 degrees Celsius, the VLP could attach itself to the host cell surface and at 37 degrees Celsius (normal human body temperature), it was able to enter the cell.

When the team injected a high dose of VLPs into mice in the lab, it did not affect the liver, lung, or kidney tissues. To test its immune response, they gave one primary shot and two booster shots to mice models with a gap of 15 days, after which they found a large number of antibodies generated in the blood serum of the mice. These antibodies were also capable of neutralising the live virus, the team found. “This means that they are protecting the animals,” explains Raheja.

The researchers have applied for a patent for their VLP and hope to develop it into a vaccine candidate. They also plan to study the effect of the VLP on other animal models (using the expertise of SG Ramachandra, one of the inventors), and eventually humans. Raheja says they have also developed VLPs that might be able to offer protection against the more recent variants like Omicron and other sub lineages.